CASE STUDY: The Identity Leadership of Toussaint Louverture.

Louverture; An Identity Leader

I am a believer and applier of Stedman Graham’s Identity Leadership studies, as described in his book of the same name. The author has taught me to look for leaders who exemplify Identity Leadership traits to grow myself by learning how and why they did it. One such example is Toussaint Louverture, the 18th-century leader of the then-French colony of Saint-Domingue, the precursor to the nation of Haiti. He is a man that I consider one of the greatest leaders of all time.

As Graham so eloquently points out, an identity leader must first go through a process of self-actualization, a theory developed by Abraham Maslow and his hierarchy of needs, which the author illustrates as the highest level of psychological development to facilitate your potential to be fully realized.

In the case of Toussaint Louverture, the man was born into slavery but never allowed bondage to label him or define who he was. He had a deep understanding of self, nourished in the fact that his grandfather was a king, and his father a prince, once a challenger for the throne of the Allada people, located in what is now present-day South Benin, West Africa.

Toussaint grew up a slave on the Breda plantation in the north of the French colony, eventually to be named Haiti, in the mid-1700s. From early in life, he was an overachiever; an active learner, and a sponge for knowledge with the ability to be an independent thinker and self-starter of activity. He was small for his age and nicknamed Fatras Bâton (feeble stick) by those on the plantation. He got into trouble by

The Ghost of the Savannah

standing up to young white workers, often getting into fights, when he would stand up for himself and other slaves.

By his teenage years, he had become a skilled equestrian, nicknamed Le fantôme de la savane (The ghost of the savannah), because he was so fast. He earned the trust and respect of his owner, Bayon de Libertad, who made him a coachman for his family. Libertad respected Toussaint for always protecting his peers and the assets of the plantation, at one point chasing after and throwing the family’s attorney off a horse that he had taken off the property without permission.

A skilled natural healer

Toussaint went on to study medicine and combined the methods of the Jesuit hospitals with the island’s herbal medicine. He became a veterinarian and healer of the workforce, and an innovator in the art of natural medicine and the art of healing with herbs, roots, and leaves.

He later became a theologian and devout Catholic. He built relationships easily and developed into a trusted leader of the workforce enabling him to be a skilled manager. So valuable was Toussaint to Libertad, that he was eventually freed from slavery without compensation. Libertad even assisted Toussaint in launching his own plantation business.

Never forgetting his roots, Toussaint used his profits to purchase his family and friends out of slavery until the beginning of the first slave

From healer to soldier

revolts of 1791. Bayon de Libertad’s kindness and generosity were never forgotten by Toussaint and repaid by saving his life and that of the entire family from the violence of the slave rebellion.

Toussaint was recruited into the slave army as a healer. His ability to quickly adapt, learn, understand, and embraced the enormous changes occurring during that historical period enabled him to transition into a commander of military troops, quickly outpacing the performance of his superiors who had joined the Spanish in the East to fight the French in the West. Toussaint won many battles and conquered large swaths of the French colony resulting in being bestowed military honors by the King of Spain, elevating him to the top commander of the Spanish auxiliaries.

Embracing and harnessing change

Toussaint mastered the art of warfare, continuously learning new fighting skills from his European colleagues and tactics of jungle warfare from African Maroons, enabling him to recruit, organize, and train a lethal fighting force.

When France abolished slavery in 1794, Spain continued the practice. Toussaint embraced the new change, stuck to his moral convictions, and joined with the French. With his army of over 2,000 men, Toussaint reclaimed the lands he had once conquered and returned them to the French flag. When Britain invaded the weakened

His rise to Colonial Governor-General

French colony to capture their riches and re-enslave the blacks, Toussaint waged war against the finest British generals, forcing them to flee the land and sign a peace treaty under his terms.

For his continued success and valor, the French named him Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces and Governor-General of the colony. Toussaint marched towards his vision and goal of re-establishing the economy, burdened by years of strife, and developed a labor system of compensation to replace slavery to boost production, even though unpopular with both the ex-slaves and the planter class alike.

Willing to take risks to reach his goals

Against the will of the French government, he invited white planter emigres to return to the island to reinvest in their dormant plantations, as well as entice local free people of color and ex-slaves to work in unison with each other towards his vision of peace and prosperity.

Many political rivals attempted to usurp his power, both militarily and politically, but Toussaint bested them all, sending most into exile in the process. He eventually merged the French West and the Spanish East of Hispaniola into one colony and formed a committee to create an autonomous constitution for the colony with representatives from both sides.

Diplomat and international problem solver

When the Quasi-War broke out between France and the United States, French pirates began to menace American vessels, sinking or stealing over 300 of them. The United States retaliated by outlawing trade with all French colonies, including Saint-Domingue, to cripple France economically. Toussaint immediately saw this change as an opportunity and sought a solution, sending a diplomatic envoy to President John Adams without French government approval, not with hat in hand to plead for mercy, but offering a solution to America’s piracy problem; Toussaint would fight the pirates and Adam’s would open free trade to the colony.

Toussaint’s Clause in the U.S. Congress

In 1798, the United States Congress enacted legislation that was quickly nicknamed “Toussaint’s Clause”, enabling the Adams administration to open trade, diplomatic channels, and conduct business with Toussaint’s administration if Toussaint protected American interests. Trade flourished, the economy quickly rebounded, and within a year over 1,000 ships were plying the Caribbean waters between the U.S. and Saint-Domingue. Soon, he would broker a tripartite agreement with Great Britain as well.

Unfortunately, history was forever changed by Napoleon Bonaparte who had just engineered a coup d’etat in France. He became infuriated by Toussaint’s autonomous governance, the unauthorized constitution, and a letter of introduction to him from Toussaint that contained the phrase, "From the first of the Blacks to the first of the Whites."

Napoleon set out to conquer him

Napoleon mounted the largest invasion force in history to rein in the colony’s government and military, as well as his secret plan to reintroduce slavery. It began with 112 ships, 37,000 initial soldiers, and sailors, and eventually grew to an expeditionary occupation force of 80,000 over the next two years.

Toussaint would soon be arrested and sent to die in a French prison as he refused to be subjugated to Napoleon and predicted the dictator’s ambition to re-enslave his free citizens.

This is just part of the amazing story of Toussaint Louverture, an identity leader of the 18th century who fully understood who he was, recognized his strengths and weaknesses, laid out a clear vision to better the lives of his people, was a self-starter, sought appropriate

education and risked his freedom to execute what he felt was right and just, while at the same time balancing his personal life with a loving wife, three children, and thousands of soldiers and citizens who adored him.

He lived up to Stedman Graham’s description of an Identity Leader of the times.

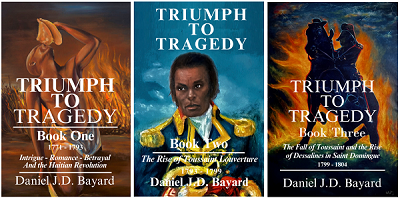

Daniel Bayard is the author of Triumph To Tragedy, a three-part trilogy wherein Toussaint Louverture plays an important role.